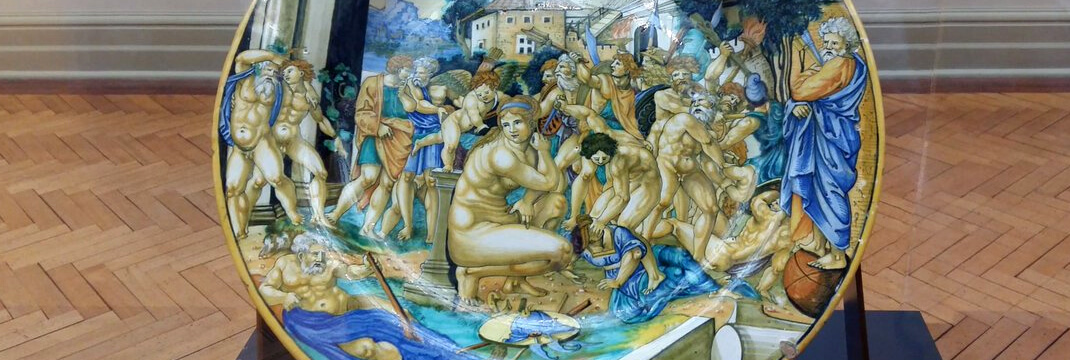

Italy has always been a home place for a variety of arts. Maiolica is a style of ceramics that originated during the Italian Renaissance. Using the tin-glazing method, Italian masters of ceramics developed complex narratives for their earthenware. Different historical events and ancient legends became subjects for colorful plates. Francesco Xanto Avelli was one of the best ceramists who developed maiolica craft and raised it up to a level of art. One of the typical examples of his work is An Allegory on The Sack of Rome plate painted in 1530. Xanto is known for depicting a subject matter in an allegorical form and adding meaningful inscriptions to better explain his allegories. Although The Sack of Rome plate is highly decorative, similar maiolica earthenware also had utilitarian and entertaining functions.

Xanto is known to have significant independence in comparison to other ceramists of his time. He signed his works and was free to pick a subject. Often, he created new plots while other ceramists simply copied existing compositions. The painting process of maiolica was difficult as glaze was quickly hardening, and it would not be easy to correct mistakes. Therefore, ceramists often copied drawings and illustrations of famous artists onto earthenware. However, Xanto afforded a great deal of flexibility by copying not complete illustrations but only parts of it. In some cases, Xanto made completely new decorative designs.

There is a series of plates painted by Xanto that refer to the historical event of the sack of Rome in 1527. Throughout the Renaissance times, Italy was not united, and each city could be an ally with another city or even another country. The Imperial troops were not paid for their previous victory over the French army, so they came to loot Rome, and the troops of Rome could not defend it. The Pope tried to flee but was imprisoned and had to pay for his release. Xanto’s The Sack of Rome plates tell different aspects of the story. A plate in Faenza, Italy, depicts the Pope’s imprisonment; a plate in Saint Petersburg, Russia, allegorically portrays how the emperor dealt with the city; a Milan plate tells about the immoral character of the city. The present plate is kept in Sydney, Australia, and, whereas the exact meaning of Xanto’s works is rarely completely clear, may suggest that Rome was “punished for its sins.”

There is much evidence to Xanto’s ambitions exceeding accomplishments of a mere craftsman. Xanto was well-read, knew poems by Petrarch and Dante, and read translations of ancient historians such as Ovid and Virgil. Being not only a distinguished painter, Xanto was very interested in poetry, and his inscriptions were “often laid out, and read, as poetry.” Another peculiarity of Xanto as a ceramist was his passion for allegories. His maiolica dishes are not illustrations on a subject but an allegorical rendering of a topic. Xanto’s intent was to make images and inscriptions work together emulating “the allegories and inscriptions on so many medal reverses.”

Invite your friends and get bonus from each order they

have made!

The plate under discussion is inscribed as follows: “On the 5th May under the patronage Juno, the lancers and Spaniards entered Rome and held Peter and Bacchus in their power History Francesco Xanto Avelli of Rovigo painted it in Urbino 1530.” Therefore, Juno, Peter, and Bacchus are the major characters of the plate along with Romans and Spanish soldiers.

As the patroness of the troops of the Holy Roman Empire, Juno is depicted sitting on a cloud at the top of the plate. On the far right, Peter is holding large keys, which symbolize his authority over heaven and earth. As a significant figure in Catholicism, Peter also is a symbol of the papacy. His teeter position of the globe suggests that it is experiencing rough times and can either regain its balance or topple off.

On the far left, Bacchus is depicted in an inebriated state together with Silenus. Since as Bacchus is a god of winemaking and an ultimate symbol of drinking. Venus together with Cupid symbolize amorous affairs. Therefore, depicted together, they may suggest that Rome under the papacy became the cradle of moral filth and debauchery, because, at that time, Bacchus and Venus were “equated with Rome.”

Among other figures that can be identified are Hercules and Mercury. Clearly supporting the Imperia troops, Hercules is brandishing his club. Mercury is deep in the throng and can be spotted by his winged helmet. On the low left, an old man symbolizes a river god. Other figures on the plate are unidentifiable soldiers and Roman citizens. In the foreground, there is a broken column which again may suggest the forthcoming chaos and disintegration of the papal power.

The plate is 46.0 cm/18.11 inches diameter and is tin-glazed earthenware. The production of tin-glazed ceramics was complicated and unsparing to an artist’s errors. Because of the technological process, ceramists had to be very attentive and meticulous. After the first firing, the ceramic object was covered with a tin- and lead-based glaze which left a white residue. Colors against the white background looked clean and bright, but the porous surface of the clay object would momentarily take up the pigment not giving any time to correct mistakes and smudges. For the second firing, the painted ceramic object was covered with a lead glaze that would fix colors and let the ceramics retain their original look till today. The third firing with a silver or copper glaze would create luster on the surface.

Top Writer Your order will be assigned to the most experienced writer in the relevant discipline. The highly demanded expert, one of our top 10 writers with the highest rate among the customers.

Hire a top writer for $4.40Xanto painted The Sack of Rome plate in 1530 when he began using strong colors in his palette. The plate is bright with turquois blue, cobalt and different shades of ochre. Experts notice that with the rise in popularity of maiolica, some ceramists began compromise on quality. Xanto’s works from the next decade suggest “hurried execution.” Whereas The Sack of Rome plate looks carefully made, certain faces do not look well-defined. In particular, next to Venus, a man is bending down to probably harm a woman at his feet. His face is given in foreshortening and looks rather awkward. When similar lapses in qualities happened, it implied that the works, or parts of works, were done by the master’s apprentices.

The inscriptions on maiolica plates suggest other functions than purely decorative. Experts believe that from being simply informational about date and place of production, the inscriptions developed into a complex cultural and promotional means. Due to the inscriptions on plates would become verbose, it suggests that there was a demand for this type of reading. Referring to important events, citing a poem or offering other pieces of interesting information, the inscriptions on maiolica dishes were a means of interaction between a host and his or her guests. These inscriptions could indicate the host’s erudition and start a conversation. Additionally, the inscriptions allowed artists to indicate their names for further commissions, thus, serving as promotional material for craftsmen.

Being an expensive craft, maiolica ceramics resided in homes of wealthy Italians. In addition to their highly decorative properties, experts think maiolica plates had also utilitarian properties. Whereas it may seem too extravagant to use richly decorated platters for actual food consumption, there is some evidence that they were used this way. Wealthy Italian aristocrats had a variety of different earthenware decorated with rich maiolica that was used during banquets such as jugs, bowls, ewers, ladles, and platters. Plates were of different sizes: smaller ones around 20 cm/4 inches were used for individual guests while larger plates around 40cm/18 inches were used for serving food. Even though such use of maiolica dishes is not confirmed by images or paintings, there is a letter dated 1528 that mentions that the Pope Clement VII had large decorated with figures for important guests like cardinals while he used simple undecorated earthenware by himself.

The maiolica plate equipped with the inscription presented a rather interactive object in the 16th century in Italy. In the article “Inscriptions and the Dynamic Reception of Italian Renaissance Maiolica,” Lisa Boutin Vitela, on the example of the David and Goliath plate by Guido Durantino, explains how maiolica plates used to function. Similar to Xanto’s river god and a stream of water in the forefront of the plate, Durantino’s earthenware also had a depiction of a river but it was placed in the center. Vitela explains, “[W]hen the dish contained liquid, the painted narrative would reveal itself to the viewer as the liquid drained from the dish echoing the path of the painted river.” Furthermore, the guest might want to confirm his or her guesses and would turn the plate over to check the inscription. Such interactive activities contributed to a large popularity of maiolica earthenware.

In Xanto’s The Sack of Rome dish, the presence of the river may also suggest a similar use when food would eventually reveal the hidden narrative on the plate. In fact, a rather circular composition of the subject on the plate indeed makes the process of dining interactive. Xanto tried to work around the round shape of the plate by arranging clouds in a semicircle in the upper top of the plate and making the flow of the river go along the lower edge of the plate. The figures of Bacchus and Peter on the left and right suggest a possible narrative to the viewer in front of a filled up plate on a banquet. Thus, Xanto intended the naked Venus as an ultimate revelation for the dining viewer by placing her at the center of the dish.

Maiolica earthenware served several purposes. Beginning with the most obvious decorative function, maiolica tableware was used to entertain the guests and supply interesting topics for conversations. The interaction between the image and the inscription was highly entertaining, and it contributed to the interest in the genre. Xanto’s The Sack of Rome is an enduring example of the 16th-century dining culture kept in perfect condition due to the technique of tin-glazing.